Last week, I encouraged you to think of publishers as drug traffickers. Now, I’ll encourage you to look at them as you would a venture capitalist. A lot of mental images pop up with the term venture capitalist. These images are usually that of younger to middle-aged men, casually wearing expensive suits as they arrogantly make high-risk gambles investments on companies that are run by smug founders, supremely confident that the dollars will effortlessly flow in. Contrast that with the image most people get when they hear book publisher. Whatever mental images people might conjure up, they are generally positive; warm-personality people who want to romantically spread a story for people who want something pleasant to read. While the images of these two professions are worlds apart, we need to realize one thing; they’re essentially the same exact thing.

For starters, there are publishing houses and venture capital firms that are large and diversified; such examples of open-minded firms are PenguinHouse for publishing and BlackRock for capital. Meanwhile, smaller boutique operations seem to pop up all the time, as they cater to a specific niche of their particular markets; there are publishing houses that cater specifically to the historical fiction genre while there are venture capitalists that exclusively fund AI companies or those with women founders. Generally, the smaller operations are more open to working with a first-time founder/author than a brand-name source of funding (let’s not pretend otherwise) would be.

Both professions make a lot of investments, and I mean, a lot of investments. Sourcing new prospects to invest their considerable war chests into is an onerous task in itself; there are countless start-up founders looking for funding (especially in this 2023 economy, given the tight labor and credit markets, along with other VC firms being more stringent with their funding) as well as authors who dream of getting signed to a publisher. Of course, venture capital firms and publishing houses both need to have ruthless filters in place to screen out the unworthy, Y-Combinator is infamous for being sticklers. Make no mistake, these are hefty financial investments; whether it would be paying for an author’s advance, marketing budget and editing expenses or a venture capitalist parting ways with a considerable amount of money upfront.

These investments are not just financial either; both lines of work command significant time for the investor into the investee. Venture capitalists are literally vested into the success of the companies in which they have poured money into. This involves coaching the founders and their management team into the best possible position to win in the marketplace. This often involves being a trusted adviser and confidant to the often-frazzled founders. But hey, don’t just take my word for it. The same is often true for publishers; many publishers spend investments of time with their authors, guiding them through the editing process, planting seeds of context to the big picture, being a sounding board for marketing and editorial decisions and more. This requires an absolute ton of patience from the investor. In this aspect, the venture capitalist and publisher are more akin to cousins than strangers.

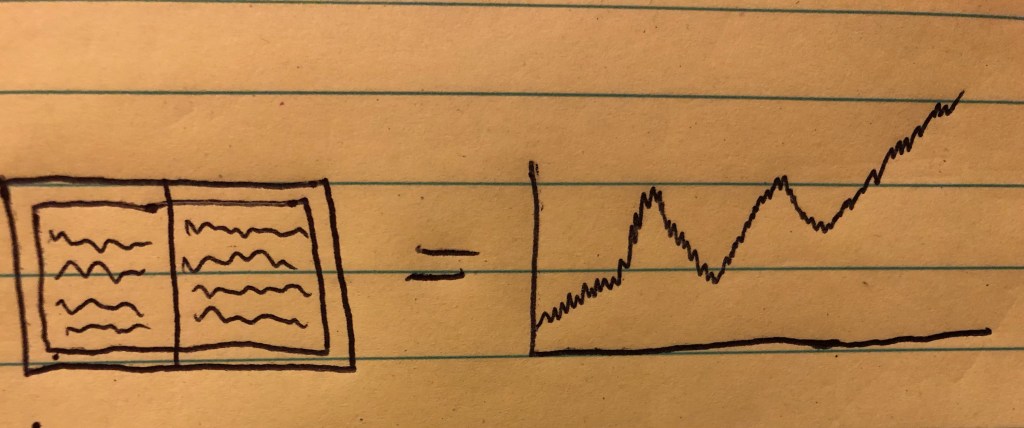

Both professions need to have high-risk tolerances, and as such, high-failure tolerances. Many new ventures fail, and that is just a part of the landscape. When a company dies, an investor can get their investment back if they are lucky, though this is not usually the case. As I’ve mentioned before, venture capital is not for the faint of heart. Similarly, only a small percentage of books out-earn their advance, thus making publishing books a risky endeavor. Given these failure rates, the incentive is clear; relentlessly filter out the non-viables, make bets on a group of promising prospects while fully realizing that only a few will yield a positive return. Not only do these profitable projects need to yield a positive return; they need to be absolute homeruns in order for the funders to remain profitable. It’s quite literally go big or go home for both the publisher and the venture capitalist. Both arenas are difficult indeed.

The long-running venture capitalist firms and publishing houses tend to survive because they find enough diamonds in the rough to generate massive profits. These profits are used to gradually consolidate the markets in their favor, and this has been especially pronounced with the Big Four publishers. In earnest, I don’t even think that this is a bad thing either; surviving such a difficult environment for so long ought to be rewarded, and boutique firms will sprout up to fund the niches that the large capital firms/publishing houses will pass on. However, it is possible for the major players to get complacent and miss out on promising rookies; J.K Rowling was turned down by numerous publishers before receiving a modest advance for the first Harry Potter book.

Spotting a diamond in the rough is hard. Being able to do so more than once is rare, and being able to do so time after time puts you in the GOAT category. To both the publisher and the venture capitalist; Happy Mining!