I have a confession to make; I’m not afraid to put down books I dislike. In fact, I do it all the time. I always read the first 100 pages or 40% of a book (whichever is greater). If I’m still not hooked, its game over, plain and simple. However, it seems like there is a taboo in admitting to this, as if putting down a poorly paced book is a sign of having commitment issues. So, today I’ll do my part in breaking the stigma, as I go over some household-name books that I gave up on for one reason or another. I’ve given every book in this article the benefit of the doubt up to the 40% threshold. “But Dan, the book doesn’t get good until..” stop it. It’s not my fault these authors can’t hook a reader.

Think and Grow Rich is a classic book by Napoleon Hill that I’ve attempted on several occasions but have never finished. Hill’s style of writing is obtuse and indirect, as evidenced by the supposed secret of wealth that he claims to be written on nearly every page of the book. However, if it was so obvious, then why can nobody agree on what it actually is (assuming it even exists)? Hill also goes on tangents that are only quassi-related to the main point of his argument. In this vein, he is similar to modern-day pundit (eww…pundits) Scott Adams. I look forward to everyone telling me how impatient and naïve I am.

The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith is another classic text that I’ve tried on more than one occasion to get through but have failed. To give credit where it’s due, Smith’s work has been foundational in the field of economics, where even writers in our modern era reference his book. However, that doesn’t change the fact that, as I mentioned last time, Smith’s book is incredibly dense, it is a poor entry to the arena of economics by itself. The Wealth of Nations almost requires a support group or a teacher to walk readers through the material in an open forum. Using Adam Smith as an entry into economics is like using Immanuel Kant as a gateway into philosophy; it’s technically possible but I wouldn’t advise it. Both Smith and Kant are best approached with some background knowledge or a guiding hand; the problem being is that while Kant is often read in this context, Smith usually isn’t. When you get finished telling me how much of a smooth-brain I am, you can get at mad at this next opinion as well; his book is very dry. The pacing is hampered down by incredibly long-winded explanations, thus making the book an absolute slog to get through. “Well Dan, you’re just naïve for expecting appropriate pacing from a book that predates the Declaration of Independence. The problem is you Dan, and not the book’s lack of copy-editing!”.

Much like Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow is another classic title that I just simply can’t muscle through. It has many of the same strengths and weaknesses. Both books are exemplary in their fields, in fact Thinking Fast and Slow has been reviewed by numerous psychology journals and sits atop many perennial best-seller/recommendation lists. However, Thinking Fast and Slow is also on a dense topic that having some background in would be helpful. Unfortunately, that is not at all how that book was marketed. Kahneman’s book sits in a strange grey area, anyone who has taken a few psychology or neuroscience classes will find his book a bit too entry-level, but anyone picking up his book completely cold will find the entry barrier too high, and it made me wonder who this book was really for. I expect all of you to either call me arrogant for being a know-it-all or a stereotypical short attention-spanned Millennial.

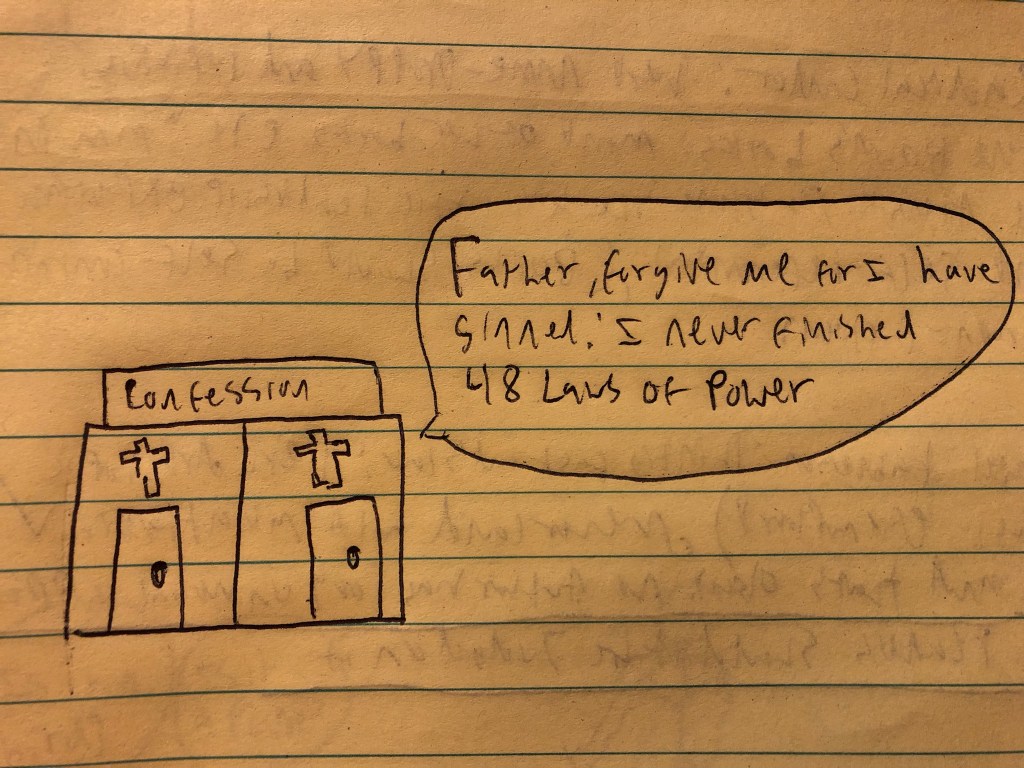

Another classic that I’ve never finished is Robert Greene’s 48 Laws of Power. Well, to be candid, I’ve never made it through any of Robert Greene’s books (The Daily Laws was an obvious low-effort cash-grab, though that’s beside the point). 48 Laws is a very useful book, and I can honestly say that I’ve used some of the lessons myself to great effect (my personal favorite is Always say less than necessary, followed closely by Never outshine the master). I almost didn’t want to mention 48 Laws because of how great the book starts out. However, the longer and longer one reads through 48 Laws, the more and more repetitive it gets. Unlike Adam Smith, who has the benefit of centuries past to shield him from pacing criticism, Greene has no such excuse for front-loading all of his useful content. There is almost no reason to seriously read past Law 27. This also says nothing of how increasingly cynical it gets. “Dan, disliking a book about obtaining power for being kind of cynical is a dumb critique to make”. Be that as it may, a book shouldn’t make its reader feel like a worse human being for progressing through it. After you’re done attacking my masculinity, I’ll thank you for confirming my critique of men’s reading culture that I alluded to in the Part I. The strange part? Robert Greene as a speaker and a podcaster doesn’t give off any of the ruthless vibes his books do; he’s a much better presenter than he is an author (either that, or Greene does not practice what he preaches). A silver lining of Greene’s career is that he mentored the incomparable Ryan Holiday. Holiday has shown to be able to keep his audience engaged and enlightened while using historical cases to prove his points.

Much like Robert Greene and 48 Laws, Kim Scott’s book Radical Candor starts off legitimately great. Her points, backed by relevant personal anecdotes, are poignant and powerful. Radical Candor tends to tail off its usefulness in its back half. Kudos to Scott for including a handy chart, however the first half of the book and the chart are all one really needs to get the gist out of it and start applying the concept. In a roundabout way, this is strength of the book, however this doesn’t alter the fact that I still have yet to complete this book and have no plans on trying it again. I hope she’ll forgive my…wait for it…Radical Candor! I’ll see myself out now.

Brene Brown is another author who I, for the life of me, just cannot make it through. I’ll explain as soon as you’re done calling me a misogynist. Ready? Okay, the academic leadership expert stuffs her books full of self-referential terms, thus making the act of picking up any of her books out of order an onerous task. Non-fiction books should not have an artificially high barrier to entry; this isn’t the Marvel Cinematic Universe or the Metal Gear Solid series. Contrary to Brown, her contemporary Simon Sinek has written several great leadership books that are all self-contained. Also, in Dare to Lead, she drops references to Theodore Roosevelt’s famed Man in the Arena speech while also confessing to having little leadership experience herself while writing her prior books. Forgive my skepticism.

If you couldn’t already tell, I was being facetious with my self-deprecating comments. As I alluded to in Part I, not liking a specific book doesn’t reflect on your character whatsoever. Broadly speaking, the culture of reading is quick to assign moral weights to readers based on their tastes (looking at you, bookstore employees) without caring about the lasting stigma. It’s also worth noting that no author has universal appeal, no matter how much we want them to, and someone who makes a reasonable attempt to read their work shouldn’t be chastised for disliking or not finishing it. Life is short, and sunk cost fallacy is real. Consider this as your permission; It’s okay to put down a bad book.