This past weekend was Thanksgiving (which for the record is one of the few true holidays left) and for the first time ever, I had deep-fried a turkey for the feast. It was a side quest that I had always wanted to do (yes, you may call me a hypocrite). However, the entire side quest served as a reminder to the virtues of understanding risk and appropriately isolating variables.

When the opportunity to embark on the side quest was presented to me, I jumped at the opportunity. I looked at numerous different sources of information online and many revealed the same basic tidbits of advice. Consensus-seeking is usually a wise move because it prevents one errant data point from skewing results, and the fact that numerous sources agreed lent a lot of legitimacy to the information presented. With that said, I spent the handful of days leading up to the feast dutifully following the instructions presented.

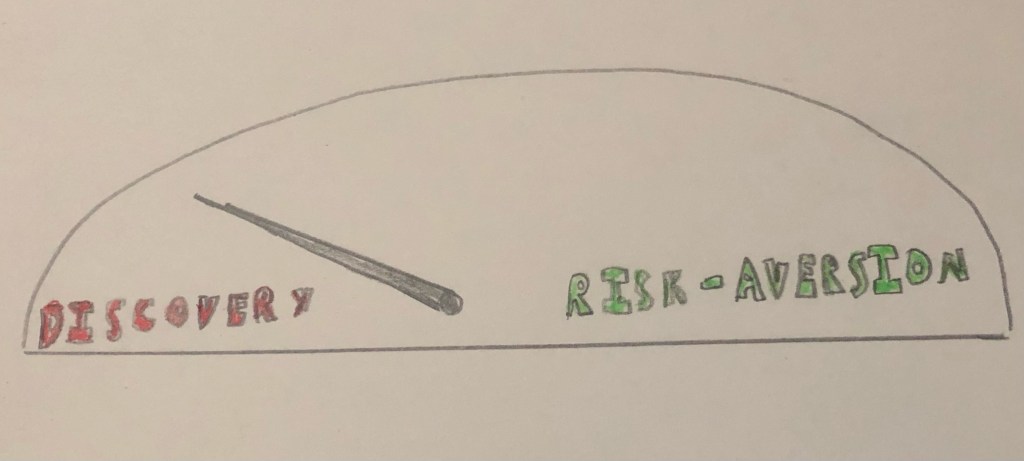

Nearly every source that I could get my digital fingers on preached the virtues of a dried-out turkey. This is understandable; after all; oil and water don’t mix, and at temperatures north of water’s boiling point, a saturated turkey is a dangerous turkey. However, try as I might, I couldn’t rid all of the moisture from the turkey carcass. This was an exercise in risk-aversion by the various turkey-frying authors; they didn’t want to be held liable for someone burning their house down, hence the overly-cautious instructions of absolutely zero moisture, despite the fact that the stated criteria is essentially a fool’s errand.

The next instance of risk aversion was hard-coded into the instructions, albeit subtly. I arrived on scene for the big day and began setting up my newly-acquired deep fryer. The flame was lit ([insert “lit” joke here]), and I carefully monitored the temperature of the oil as it slowly crept up. I sacrificed my masculinity by opening the instruction manual to the troubleshooting section, only to find an unhelpfully short guide. The guide included instructions for a flame not being lit at all (like wearing crocs!) and what the ideal flame should look like. However, information on how to actually attain the ideal flame was virtually nonexistent. Thus, I embarked to figure out the conundrum of the blue flame on my own, by visiting one variable at a time. I spent the next thirty minutes attempting to tweak the flames under the pot. First, I slowly increased the gas supply to the burner. Next, I tweaked the flow of air into the burner, which yielded a much truer blue flame.

This omission was a sly move of risk aversion on the part of the manufacturer of the deep fryer kit. The author of this manual was trying to avoid a liability lawsuit (as we are a very litigious culture) by omitting instructions on attaining a true-blue flame. Instructional documents written for consumers typically come with a long list of disclaimers before activities that are particularly spicy, yet the authors of this instructional manual chose to be overly risk-averse and side-step the issue entirely. As someone with five years of professional technical writing experience, I find this blatant skimping of details to be abhorrent, even if the endgame was plausible deniability.

The oil reached the minimum desired temperature of 350 Fahrenheit (or about 177 Celsius for non-native speakers of Freedom Units!) and I slowly drop the turkey into the vat of hot oil. It was a nerve wracking, though thankfully uneventful, moment. The temperature of the oil dropped as it understandably should have; the bird carcass was no more than 40 F (8 C for nations that haven’t stepped on the moon). However, the temperature had a hard time rebounding with my current flame. Using the same variable-isolating approach as before, I found the issue this time was there wasn’t enough gas supply to compensate for the introduction of cold poultry (coultry?), so this was a pretty easy problem to solve for.

With that said, nearly every set of instructions; from the manufacturers of the frying kit, to the industrial farming corporation that bred my future meal, to big-time celebrity chefs all recommended that the temperature return to 350F as fast as humanly possible. Any lower, and the bird risks burning and the home chef risks having oil seep into the meat of the bird. The oil dipped to as low as 250 F (roughly 110 C, for those who think football involves continuous light jogging and a round white ball) for about thirty minutes. My variable-tweaks only managed to get the heat back up to 350F for the final 10 minutes or so of the deep fry. However, the end result yielded no oily meat beneath the skin, nor did I see any overly blackened ends.

Every published source generally agreed that the bird needed to fry for at least 4 minutes per pound (or four minutes per half-kilo, for those who enjoy metallic-tasting bottled water). However, even with struggling to get the heat up to the recommended temperature after the bird submersion (sub-bird-sion?), the star of the feast fried much sooner than the calculated time. Using a meat thermometer to confirm that the bird had indeed reached the safe consumption temperature, I turned off the burner, disconnected the propane and headed indoors, curious to taste the end result.

This was risk aversion rearing its ugly head again. The culinary world is a risk averse one; food safety guidelines are written for the lowest common denominator of the healthcare system: little old ladies, small children, the immune-compromised, and so on. Thus, the heating and time instructions were artificially padded to remove the slightest hint of possibility that a weakened pathogen might survive. The truth is, that for most of us, our immune systems are good: like, really good. However, nearly every published source of instructions feared a lawsuit, hence the instructions provided would kill all potential liabilities, along with the texture of the meat. Had I followed the professional advice to the letter, I would have undoubtedly received a burnt, dried bird with Thanksgiving ruined; I’d rather risk a knife fight over a new TV than ruin Thanksgiving.

The feast began in short order, with all participants eager to try the poultry. I had received kudos for how the bird came out. However, my New England compliment-deflecting cultural programming along with my scientific training meant that I couldn’t help but to run through how I was going to tweak certain variables for next time. However, a lot of knowledge came from this initial attempt. Future Thanksgivings will involve a much more open-air flow with limited gas pre-bird, a high post-submersion gas flow, and a shorter time (now that I have some working data points). Qualitatively, I’d change the dry-brine seasoning; some salt is needed to dry the turkey, though I played too conservatively with the rest of the spices.

Change the world, one variable at a time…